In the attempt to read Beirut, I propose a brief overview of its public spaces through time. Since the very early stages of the city’s development, public spaces had been associated with exogenous interventions. Among the visible traces are the Roman baths and the Roman Cardo and Decumanos, currently the Ma’arad - Allenby and Weygand Streets.

With few exceptions, the available public spaces result from the overlay of different eras and political climates. Exceptions include the spaces within the reconstructed city centre managed by the real estate company Solidere, which are a response to the company’s strategy to promote property. Further, private initiatives to provide public spaces are emerging across the city.

Public spaces dating back to the Ottoman period include the Sanayeh Garden, the Serail and its gardens, Sahat Al Sur (Riadh Solh Square) and the Corniche. These were construed as instruments to modernise the city following the example of Istanbul, and to reinforce the reign of the Empire over Beirut. The city was reshaped during the French Mandate period to reflect the French way of living with its cafés, cinemas and promenades, but further to set the stepping stone towards establishing an independent Lebanese state.Traces of these spaces include Sahat Al Hamidiyah (Martyrs Square), Place de l’Etoile, the Pine Forest, and the Corniche, planned in Ottoman times.

After independence, French experts prepared several plans for Beirut with varying emphasis on its public spaces and a focus on the transportation network and the urban expansion related to population growth. The currently adapted 1954 Ecochard Plan, based on his 1944 Plan, indicated the importance of public spaces. However, little beyond streets was executed as open spaces. Through later plans, the public space factor was slowly diluted at the expense of private development interests. This resulted in the current dense urban fabric with rare breathing spaces shared by an ever growing population.

During the 1975 war period, with the evacuation of the city centre, social and physical fragmentation along the Damascus Road demarcation line came the annihilation of public spaces including major squares, and transportation hubs and their conversion to militia spaces. This eradication caused a distortion in the socio-cultural Beirutee framework and a huge gap in people’s everyday public lives.

The post-war efforts to rejoin the divided city and reinstate its public spaces were limited to unrealised intentions. Beirut’s few public spaces struggled to regenerate or else changed their publicness according to their disposition in the city. In the city centre, urban planners in Solidere have emphasised their efforts to reintroduce public spaces at various urban scales as the bonding agent for the war-torn population.

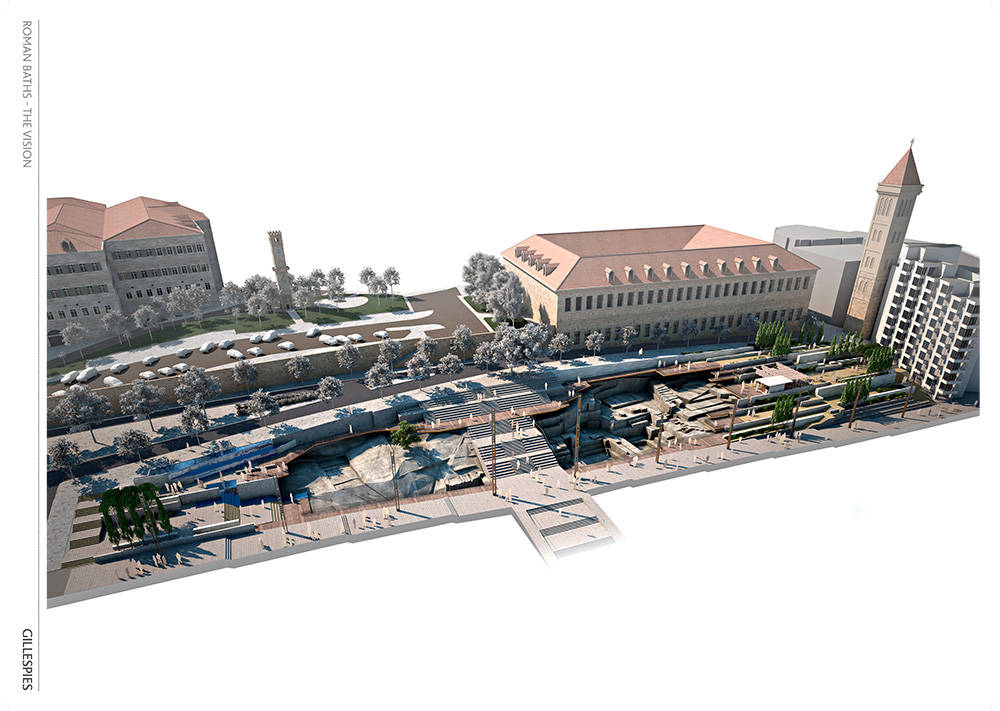

However, securing the publicness of these spaces is still ambiguous, especially with security concerns, limited access and the spaces’ surrounding land uses. The Roman Baths Park is an example of a public-less space. Moreover, the orchestrators of the project have not indicated how the centre would connect to the rest of the city and its population. In March 2005 Martyrs Square was reclaimed by the Lebanese thus altering the image of the city centre and putting in question Beirut’s public spaces.

The volatile situation in the city resulted in temporal and spatial adaptations to collective practices in the absence of public spaces. Formal municipal provisions and laissez-faire attitudes contributed to the current state of public spaces that serve war-fragmented publics.

In addition to its inherited public spaces, Beirut’s unlabelled temporary public spaces help determine how various publics deal with issues of security, relocated or vanished sites, collective memory, and territoriality. This includes the minutia of plants on a porch to the use of a vacant lot for sports. These grass roots initiatives throughout the city are evidence of a response to urgent needs.

Christine Mady is Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, FAAD,

and contributes to courses within the Masters in Design Program. She has professional experience in architecture and urban planning in Lebanon and abroad. Her areas of expertise covered planning practice, inclusive design and planning, planning for the enhancement of natural and cultural heritage, and public spaces within the built environment.