From the biological to the geological.

If mere survival, mere continuance, is of interest, then the harder sorts of rocks, such as granite, have to be put at the top of the list as the most successful among macroscopic entities. …But the rock's way of staying in the game is different from the way of living things. The rock, we may say, resists change; it stays put, unchanging. The living thing escapes change either by correcting change or changing itself to meet change or by incorporating change into its own being.

Gregory Bateson

For the past two decades, the dominant working metaphor in advanced architecture has been biological: a desire to make architecture more lifelike, that is to say, more fluid, quicker, and responsive to change. Working from D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s description of natural form as a “diagram of forces,” advanced computer technology has been used to simulate the active forces that shape biological form. These contemporary strategies of animate form go beyond the bio-morphism of the 1950s and ’60s by suggesting that the architect does not so much imitate the forms of nature as model the natural process of form generation. With contemporary digital technology, for example, it is now possible to evolve new formal configurations in response to specific forces and constraints: structural, climactic, or programmatic. While this has produced compelling results, there are conceptual and procedural limits. The design techniques used to generate these new buildings may be dynamic, but the buildings themselves are static – if they move at all, they move very slowly. The forms generated may resemble nature, but they retain little of the performative or adaptive complexity of life.

Old ideas of the building as body persist, and the potential of metabolic exchange or co-evolution with a shifting context is limited. Moreover, despite advances in fabrication technology, a large gap still exists between the fluid, curvilinear forms generated by the software and the intractability of materials and construction logistics. Buildings – like the ground – are hard, stubborn, and slow.

Arising out of similar ambitions, a counter-trend looks not to the biology of individual species but to the collective behavior of ecological systems as a model for cities, buildings and landscapes. Landscapes change and evolve, and are also shaped by force and resistance working over time. But the rate of change in a landscape or an ecological system is far slower than that of an individual living body. Architecture is situated between the biological and the geological – slower then living beings but faster than the underlying geology. It follows from this that working concepts from landscape and ecology – which describe the complex interactions of species and environment over long time periods – offer more fitting models for architecture and urbanism than the current fascination with biological form and captured movement. Resistance and change are both at work in contemporary design production: the hardness of the rock and the fluid adaptability of living things.

This interplay recognizes that all evolution is co-evolution. Individual species and their environments change and evolve on parallel courses, constantly exchanging information. Ecologies, unlike buildings, do not respect borders. Instead they range across territories, and establish complex relations operating simultaneously at multiple scales, from microscopic to regional. In the design of a city, landscape, or territory, the question of process is shifted from design process – the short and limited province of the discipline – to the long life of a building, city, or landscape over time, enmeshed in complex social and cultural formations.

But if an ‘ecological’ urbanism is to be more than a metaphor, it needs to address the logistics of practice. What are the real and practical limits to designed intervention within the complex, shifting dynamic of the contemporary city? Cities, unlike buildings, are difficult to delimit and fix in time. Architects are more fascinated than ever with big cities, but at the same time are less and less able to control the form of the city. A further lesson from Bateson: such a complex system, by definition, cannot be designed. Everything we value about cites arises as something in excess of designed intentionality or engineered performance. The question then is how to design for unpredictability and excess. The city is an intense locus of innovation, its collective creativity always in advance of the disciplines of architecture or urbanism that attempt to control it. Contemporary urbanism needs techniques capable of engaging the real complexity of the city as the technologies, politics, social life and economic engines of urbanism continue to change.

There is a growing awareness that today’s complex design challenges can only be effectively addressed by an exchange of information among many disciplines. We need to work within an expanded field that includes architecture, urban design, landscape, infrastructure, ecology and program, and we need to factor in economics and policy. However, in such a dispersed field, it is easy to see how the specificity of architectural expertise can become diluted. In part, this was the founding premise of landscape urbanism: situated at the point of intersection between regional ecology, infrastructure, open space design, and architecture, landscape urbanism exploited its status as a “minor” field, (lacking a strong disciplinary history) to present itself as a synthetic discipline that could work on the borders of these related areas of expertise. Landscape urbanism works not only in the void spaces between buildings, roadways, infrastructure, but in the space between disciplines as well. But as promising as these ideas are in theory, to date the realized projects of landscape urbanism have stayed within the conventional boundaries of landscape architecture, primarily the design of urban parks and waterfronts, reinforcing the conventional expertise of the landscape architect.

An expanded institutional definition is still required, one which would leverage architectural expertise in the design of systems and infrastructure: a shift from landscape urbanism to landscape infrastructures.

Infrastructural urbanism revisited.

There is a principle specific to environmental ecology: it states that anything is possible – the worst disasters or the most flexible evolutions.

Félix Guattari

Revisiting the intersection of urbanism, landscape and infrastructure, seen today in the context of the 12 year history of landscape urbanism, suggests a productive way forward. Incorporating lessons from the dispersed field of landscape urbanism, this renewed attention to infrastructure represents a reassertion of the specificity of architectural expertise in the design of large scale systems and structures. The design of infrastructure offers a pathway into the complexity of the urban system where design matters: nobody questions the need to design urban infrastructure. What is required is a new mindset that might see the design of infrastructure not as simply performing to minimum engineering standards, but as capable of triggering complex and unpredictable urban effects in excess of its designed capacity. More than 40 years ago, Hans Hollein collaged the image of a warship into the natural landscape, suggesting a radical discontinuity between nature and technology. Today his vision can be seen as an anticipation of the present environmental impasse, or alternatively, as a starting point to rethink the relationship between nature and culture under the new domain of contemporary ecological theories.

This new territory has been the focus of the work of SAA/Stan Allen Architect in large-scale urban projects of the past five years. Although not comprehensive, three primary working strategies may be identified that link back to earlier speculations on infrastructural urbanism while at the same time pointing forward to new techniques and new urban possibilities. Connectivity.

Connection is infrastructure’s primary mode of operation. Infrastructures work to move goods, people, energy and information around, establishing pathways and nodes that make connectivity possible. Infrastructures themselves are static, but they serve movement. To shift attention to the design of infrastructure is therefore to get out of the double bind of frozen movement or animate form.

If conventional engineering design of infrastructure is based on linear systems, and respects the principles of separation of movement and the minimization of conflict, one valuable lesson from landscape is the potential of connections made not through lines but through expansive surface conditions. These surfaces have the capacity to multiply forms of connectivity. Surface is the territory of landscape, and these warped or folded surfaces contrast to architecture’s vertical dimension, which has become associated with partitioned space. Working with surface connectivity, the vertical axis is materialized as building and the horizontal as infrastructure and landscape. This suggests an idea of site as a continuous matrix, differentiated locally as movement, building, infrastructure or open space. The horizontal and the vertical are woven together, and both are understood as architectural material.

At the Yan-Ping Waterfront, on a site characterized by the presence of large-scale infrastructures, our task was to create a new public waterfront. This could not be accomplished by conventional landscape design strategies. Instead, we proposed the reconfiguration of a major component of the urban infrastructure – the 8.3 meter high floodwall which presently cuts the city off from the river. In place of the single wall at the edge of the city, we proposed a system of elevated levee structures – shaped surfaces that open the site to unimpeded access, and at the same time, create a variety of spaces and programs at the waterfront edge. We maintain the same level of flood protection, but we increase the number of access points and reinforce the connectivity between park and city.

The specific potentials of connections made by surfaces are exploited to open the city to the waterfront, at the same time as the essentially constructed nature of such a large scale system is respected. The proposal is a large, continuous piece of architecture functioning at the scale of the city.

Architectural specificity/Programmatic indeterminacy.Landscape offers architecture new models for thinking about the relationship between program and site. In the first instance, there is a promise that on an open field, anything can happen: sports, festivals, demonstrations, fairs, festivals, concerts or picnics, as well as any number of informal, unscripted events. In part this is an effect of scale – landscapes are bigger than buildings, but it also has to do with the openness of the landscape field. But that openness is deceiving. The field needs to be ‘irrigated with potential,’ to use Rem Koolhaas’ suggestive phrase. That is to say, infrastructure creates concentrations of density that in turn trigger concentrations of activity. Program can never be scripted per se; the necessary freedom of the urban realm depends not on top-down determinations but on bottom-up, collective formations. The limits of design need to be strategically reworked to leverage architecture’s potential to specify movement, create attractors and loosely steer program. The field is never neutral, and it is infrastructure that creates difference and the possibility for a vital life in time, organized collectively by the multitude of possible inhabitants. Gwanggyo Pier Lakeside Park was an invited submission to an international landscape competition. The competition brief called for an urban park that will become the primary open space for a planned city of 16,000 inhabitants. Two existing reservoirs are the most important landmarks on the site. However, the available land around these reservoirs is limited in size and discontinuous in plan. Massive development threatens to marginalize the open space and to fracture already fragile ecologies. In response to the need to create a viable and iconic new park-space, we proposed an integrated ‘field’ strategy of landscape restoration alongside a new ‘pier’ structure that bridges land and water.

The resulting mega-form synthesizes landscape, infrastructure and architecture. It creates a legible icon that will give the park a new identity, capable of holding its own against the development planned on site. The pier itself is densely programmed to activate the site with movement and a variety of new uses. By consolidating all active uses on one strip, the pier serves to protect the remainder of the site for quiet recreation. The landscape restoration strategy extends and diversifies the local ecologies. The landscape infrastructure strategy not only minimizes the environmental impact and energy use of the park and its facilities, it returns clean water to the eco-system, restores the landscape, and generates energy that will enable the park to become self sufficient over time.

Anticipatory design.

In recent architecture and landscape there is a fascination with self-organization and emergence – the notion that if the correct variables are identified through analysis, the design proposal will ‘emerge’ through self-organization. But the idea that self-organization and emergence are associated with lack design intention is a misunderstanding of fundamental principles of ecology, based on a loose appeal to ideas of ecological succession. Emergence does not happen in a vacuum. It is triggered by differences and imbalances in the initial conditions. In the urban or landscape realm – where we are talking about artificial ecologies - you don’t get emergence without carefully designed initial conditions. The architect’s obligation to design those initial conditions with a high degree of precision and specificity remains.

As Jim Corner has observed, “urban infrastructure sows the seeds of future possibility, staging the ground for both uncertainty and promise. The preparation of surfaces for future appropriation differs from merely formal interest in single surface construction. It is more strategic, emphasizing means over ends, and operational logic over compositional design.”

The design of infrastructure is therefore open and anticipatory. It has nothing to do with a specific message; rather, it is the design of the system that makes it possible to send any number of messages. It is for this reason that infrastructure is broadly democratic. It represents the investment by the state into systems that allow the movement and exchange of information without specifying the content of that information or the range of movement. This is not to say that infrastructures are utopian; infrastructures are systems of control as well. They can be easily regulated by switches and checkpoints, and shut down when required. And the operation of infrastructural systems depends as much on maintaining separation as it does in establishing connections. Yet we know there is always something slightly out of control when infrastructure proliferates.

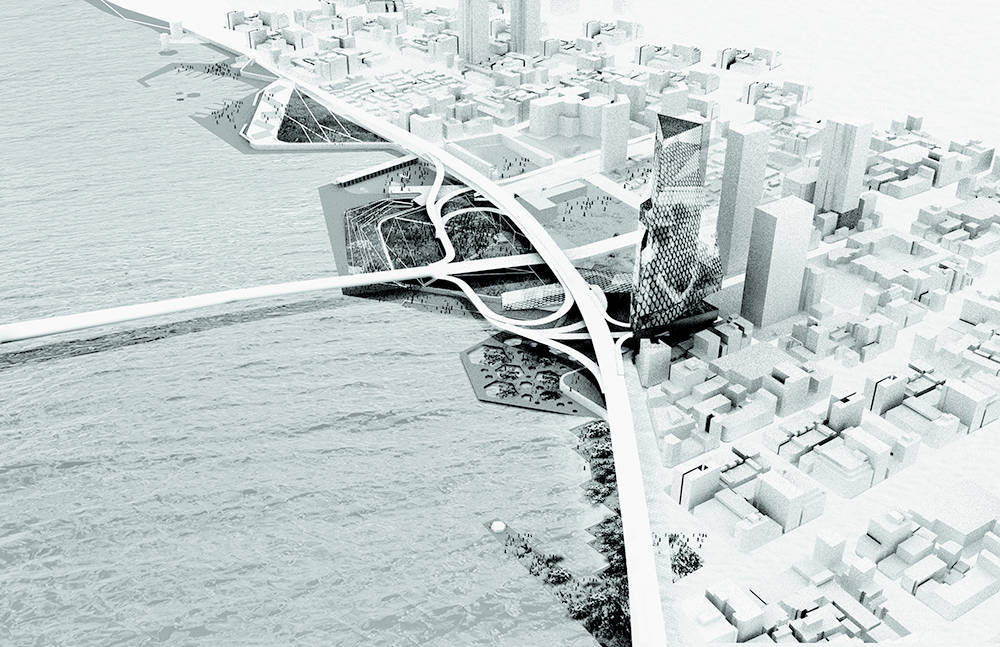

Our 2008 master-plan for Taichung Gateway Park emerged out of a clear sense of what could be designed and what needed to be left open to change. The design intention is focused on that which the city government could reasonably expect to control: public open space and roadways. The park and roadway system create a dynamic patch landscape, colonized by plant life, traversed by roads and pathways, populated with people and pavilions, and activated by periodic events and festivals. The ‘void’ of the park is not passive; it is an active, living landscape that performs infrastructural work, moving energy and matter around the site, and helping to restore the natural and social ecologies of the site.

If the park can be designed and controlled with a reasonably high level of specificity, the surrounding urban fabric can only be loosely steered over time. The city is a dynamic system, possessing its own momentum, and the figural void of the park represents a limit which will be defined over time as the city grows up to that line, marking its edge as an absence. At the same time, the park is an attractor, enhancing real-estate value, and triggering local development. Here our task as architects was simply to create a scaffolding for the city to grow in over time. The tools to accomplish this are more conventional: a simple grid aligned with existing streets, a circulation system to irrigate the site with potential, and the application of familiar conventions of urban design.

We resist the avant-gardism that would insist on reinventing everything within the project boundary, and accept the fact that the city will be financed, designed and built by others, in ways that we can only loosely predict and control.

There is a third element that functions to complicate this binary opposition of the void and the full. At the north end of the site we designed an active infrastructural presence that bridges park and urban fabric. In these large, interconnected, multi-functional buildings, architecture’s ability to fix form and structure with high levels of precision comes more directly into play.

These vast civic and commercial structures – a transit hub, a convention center and a sports arena – give an immediate architectural identity to the site through the deployment of architecture at the scale of infrastructure. They frame and shape public open space, and create infrastructural platforms for a variety of public and private functions, including an extensive shopping concourse. Three hotel towers punctuate the urban space, and create complex parallax effects as the viewer moves in and around the site on foot or by car.

Postscript: From Field to Object.

The city today is too complex for unitary strategies or ideological statements. It requires a pragmatic mix of techniques, which parallels the multiplicity of the city itself. Infrastructure plays a key role in each of these projects but it is one among many strategies. Each of these three sites is large enough to support a diverse programmatic ecology, and we deploy – without apology – an eclectic sampling of techniques, new and old.

We have learned from the experiments of landscape urbanism and landscape ecology. The roadways and civic platforms appeal to ideas of infrastructural urbanism. The architectural strategy in the large buildings, while stylistically distinct, is not so far from Aldo Rossi’s idea of the architecture of the city, elaborated now nearly 50 years ago. “By architecture of the city” Rossi wrote, “we mean two different things: first the city seen as a gigantic man-made object, a work of engineering and architecture that is large and complex and growing over time; second, certain more limited but still crucial aspects of the city, namely urban artifacts, which like the city itself are characterized by their own history and thus by their own form.” This confirms that current strategies of landscape infrastructure belong deeply to the history of architecture’s techniques; yet at the same time these old strategies can be reworked in the present with new design tools, new intellectual templates and new ways of asking questions of architectural expertise.

John Whiteman once remarked that the pavilion is the essay form of architecture, and indeed in the twentieth century it was through the construction of temporary exhibition structures that major new innovations first appeared, in pavilions built by Melnikov, van der Rohe or Le Corbusier, among others. In 2009, the master-plan for the former Municipal Airport in Taichung was accepted by the city government and implementation is underway. In order to raise awareness of the project, and to bring the public onto this spectacular site, we designed a temporary exhibition pavilion to display the site and the project. The Taichung InfoBox was completed in 2010, constructed inside an existing hanger with a clear view of the vast site of the new park. Drawings, models and animations are displayed within, and an elevated overlook terrace gives the public an opportunity to observe firsthand the transformation of the city. Construction of the InfoBox inside one of the existing hangers on site was a cost effective way to realize the project while also working to leverage the architectural potential of this iconic structure. By re-cycling an existing building we foreground the history of the airport site at the same time looking forward to a new occupation of the site in the future. Responding to the need for fast implementation and making the most of a limited budget, the InfoBox re-purposes the ubiquitous bamboo scaffolding technology seen all over Asia. All materials will be recycled at the end of the pavilion’s lifespan. The scaffolding is used to define a simple volume, a “bamboo forest,” out of which the sequence of exhibition spaces is carved. The use of bamboo is both culturally relevant and visually rich; it creates a dense weave of lightweight structural elements, which constantly change as the visitor moves through the structure.

Stan Allen is an American architect, theorist and former dean of the School of Architecture at Princeton University. He received a B.A. from Brown University, a B.Arch. from the Cooper Union and an M.Arch. from Princeton University and has worked in the offices of Richard Meier and Rafael Moneo. He was formerly the director, with landscape architect James Corner, of Field Operations. His practice, Stan Allen Architect, is based in Brooklyn.

Responding to the complexity of the modern city, Allen has developed an extensive catalogue of urbanistic strategies, in particular looking at field theory, landscape architecture and ecology as models to revitalize the practices of urban design. His urban projects have been published in Points and Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999) and his theoretical essays in Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation, published in 2000 by G+B Arts in their Critical Voices series. A revised edition of this book was published in 2009 by Routledge. He lectures and publishes extensively, both in the U.S. and abroad, and participates in numerous international design conferences and symposia.

In addition to design awards and competition prizes, Allen has been awarded Fellowships in Architecture from the New York Foundation for the Arts, The New York State Council on the Arts,

a Design Arts Grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Graham Foundation Grant, and

a President‘s Citation from The Cooper Union in 2002.