A certain kind of literature, usually defined as “science fiction”, has very often observed human conduct and desires so crudely as to profile it with the greatest truthfulness and the least cultural and moral justification. With the pretext of looking at the future, the great authors of the genre have described their present, its vices and ambitions and, without any rhetoric, they have tried to imagine the possible consequences of the most intimate desires and aspirations of their society. Sometimes with a touch of catastrophism, and free of all utopianism – even if this may appear contradictory – they have used the image of the future as a cutting judgment on trends that already exist in their society. It is futile to verify their premonitions after the fact, as their aim has been to understand the contemporary reality, even if through a deforming and fantasizing mirror, to warn against possible futures rather than to suggest them.

This is why it is impossible, in relation to the theme of this issue of area, not to recall one of the most famous stories of J. G. Ballard that centres precisely on the social dynamics triggered within an innovative condominium, part of an ambitious project aimed at the development of a city.

A skyscraper like the one in the novel is not just a “great” architecture, an example of structural, distributive, linguistic and stylistic solutions characteristic of a large building; on the contrary, it is the true framework that unites, and separates, a complex fragment of humanity. Such a building does not take the form of just any tower; it is a true social pyramid, well defined in its relations and hierarchies, in its services and opportunities.

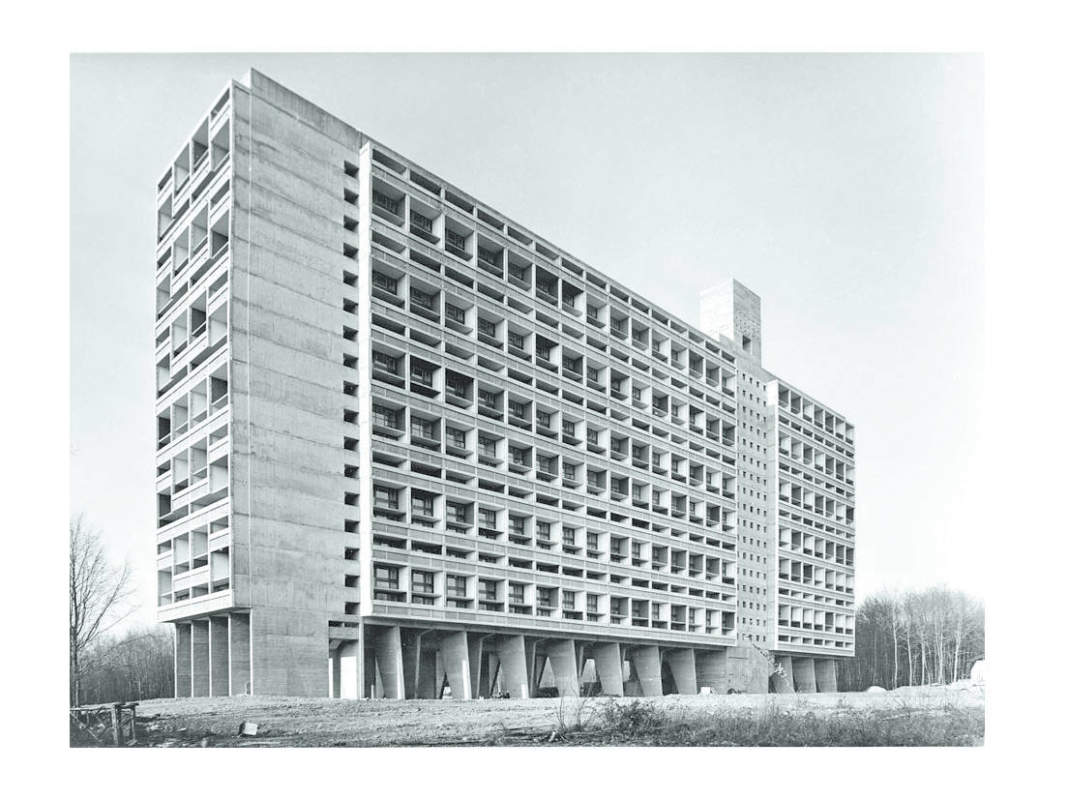

A condominium3 is therefore a complex aggregation of private properties connected by shared or public parts, and the social idea that meets these requirements is one of sharing rather than of intimacy. Such a building, regardless of its size, location or morphology, puts the needs and hopes of distinct individuals into contact; dynamics comparable to those of a whole city develop within it, triggering relations, and sometimes also conflicts, characteristic of certain social unities. As the urban form is determined by bonds of association and public assistance, hierarchic expression of private life and collective needs, likewise a condominium stages a smaller version of the same relations, even if on an architectural scale. Residential buildings housing several families are, when they are not a banal aggregation of apartments without any significant form but an intensive exploitation of space, the expression of an idea of community, organized around itineraries and spaces that represent its very reason for existing; an example of the relationship that is established between private life and public participation, between privacy and sharing, between independence and responsibility. With respect to the city, large residential blocks have played different roles over time that may be exemplified in two principal modes: either as parts of a whole, components of a connective tissue where individuals participate chorally; or as individualities with a strong character, inserted in a territory characterized by relations rather than by plots. Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation, is an example of the latter category; in fact, these buildings are not merely complex and multifunctional, but part of an innovative idea of anthropized space, enunciated since the project of the Ville Radieuse, where the dissolution of the urban space, as it has been historically conceived, is not accomplished through a cancellation of human relations, but rather through the destruction of the consolidated bonds between density and distribution, between form of the territory and dimension of architecture.

Analogously, the ideas of Archigram, precisely on the basis of the relationship between single dwelling unit and its possible aggregations, seek to suggest completely new urban forms, equally unusual as they are sometimes “unstable”, based on substantial and not formal social relations, on existential relations and convergences that are also capable of offering a new idea of public space, a new expressive form of community. This is why no twisting of theories is required to recognize, in the compositive scheme of a system of aggregation of housing units, not just the solution to the needs of individuals but also the realization of an idea capable of giving form to a “togetherness”, of giving new meaning to sharing the environment in which one lives. To see corridors as internal streets, halls and landings as squares, terraces as lookouts, porches as stoá, means to try to elevate the distributive elements of an architecture to significant parts of a public living. In fact, the present-day city is not only the planned one; it has become a complex system of relations and exchanges, sometimes intangible, in any case disintegrated and diffused, incapable of being expressed in precise form and language. This is why the contemporary instability of borders, as well as of pertinent and absolute definitions, makes it possible for the project of a single architecture to trigger an ampler reflection on the bonds and dynamics characterizing present-day society.

Finally, we may synthetically identify a number of characteristics useful for the definition of these buildings: repetitiveness, identity, perception, participation, efficiency, freedom. Repetitiveness is a negative characteristic when it represents a banal interpretation of a plan, repeated without any criterion but a functional one that makes Man feel ill at ease and unable to understand the places where he lives. On the contrary, it becomes positive when it is understood as extension of the principles of domesticity, of the value of the private sphere of the whole aggregate, when one is in other words able to avoid formal replication in favour of a multiplication of contents.

Perception is a value that must be seen in the dual aspect of “interior” and “exterior”. The legibility of the interior implies the recognisability, the identity, of one’s own habitat in addition to communication of what one is. Perception of the surroundings from one’s private space entails, on the contrary, a hierarchy of significances aimed at filtering and guiding an understanding of the world Participation makes Man play an active role in relation to the causes determining the transition between city and domestic space, between exterior and interior, between a public way of life and the building of one’s private. A relationship made of compromises with the surroundings that analyzes and defines the flows of stimuli and contacts, tracing the inviolable border of intimacy.

Efficiency, not understood as efficiency of performance, is the need to integrate individual primary needs with others of a collective kind. It is therefore the possibility to contaminate intimacy with measured and focused relations, aimed at creating a network of connections and exchanges, not yet completely public, but nevertheless no longer exclusively private. These requirements are characteristic of present-day life, in which some actions are not due or obligatory but “chosen”, and serve to realize a personal lifestyle. Finally freedom, understood as ability to suggest and not to impose, avoiding to resolve in a stable form, instead allowing for infinite degrees of discovery and invention in the fruition of spaces, in the way to use the interiors, choose the itineraries, in the characterization of the environments and in the flexibility of the components it is made of. To do so, there is no need for projections into the future, for imagining the unimaginable; it is only necessary to restore its historical task to architecture, namely that of giving form, critically, to the dreams of Man.

City in a box

area 118

| condominium