Modernity, ever since Baudelaire for literature, the Impressionists for painting, Wagner for music, has often consisted of the figure (antagonistic and secretly nihilistic) of unidirectionalism, demythologisation and desacralisation. With the consequence of the triumph of imperialism of the new Reason. In these desolate lands, the West exerts its taste, imagination, and heuristics within an extremely subjective aura of freedom, where each individual regulates him/herself in the context of poetry, the arts (traditional and new), and religion with personal and homemade inventions. Nowadays, in the West, as René Guénon writes, we are no longer heirs to anyone. At the same time, however, we realize that the lack of roots and support points in grids of reassuring certainty leads to a latent sense of loss, as revealed by psychoanalysts, sociologists and anthropologists, in response to the reactions of individuals and communities to the pressing threats of terrorism and religious fundamentalism.

But for a long time however, consciously or not, an increasing need has arisen, in terms of artistic poetry and not only, on the part of our times, to question and taste an indefinable mythical background, to explore new frontiers of relationalism, also with our history and with our unknown archaeology of the subsoil of consciousness, as well as with the potentialities of the imaginary, never deadened and in the process of awakening and enhancement. On the new horizon of expectation, of course, as if at the dawn of another vital cycle, the methods and instruments of approach can only be adapted to the Zeitgeist of this world, which Baudrillard calls “posthumous“ (post-truth, post-materiality, post-tangibility). Basically, founded on new grids, where the conceptual, virtual, experimental, and the image itself are connotative figures. Where space can be opened, browsed, enjoyed in its suspensions of wonder and amazement, revealed in its dynamic interpretation.

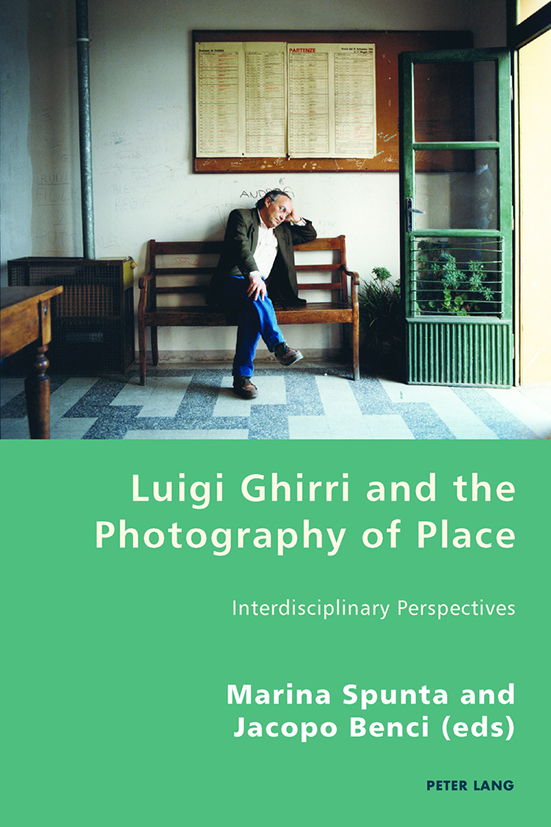

Exemplary is the case of Luigi Ghirri. A photographer, an artist with extraordinary resources, who uses photography to narrate places as realities all to be discovered, far beyond the predictable patterns of customary and passive receptions, and to change the ordinary notion of landscape. The book by Marina Spuria and Jacopo Benci, two Italian scholars from different backgrounds, who basically live abroad, helps us to discover this itinerary. Both equipped and handy users of the interdisciplinary approach are distinguished by the fact that Spuria is fully involved in critical research, while Benci is also versatile in his creativity in terms of photography, but with clear artistic intentions inspired by conceptuality.

Luigi Ghirri, to whom their monograph is dedicated, has launched a campaign of photo enhancement as a medium, which opens the doors to the epiphany of the unusual and even the unsettling, in a psychoanalytic sense, as a reality right before everyone’s eyes, in the manner of Poe’s stolen Letter, but which is not intercepted by an offhand glance and by its assumptions of possessing everything. An enthusiast of American culture, from Walker Evans to William Eggleston, who already at the time of the New Deal was tackling the essential prospect of confrontation with places, also came into contact with Aldo Rossi, by whom he was influenced in his scales of the elementary elements on the landscape. Gradually and increasingly refined is his way of inquiring about the “uncertain zone” (the “Zwischenstellung“) of landscapes and places, which is usually latent behind the deceptive threshold of standardised and vernacular forms. This is a reality, which is there waiting to be exposed to the sunlight, to enter and acquire citizenship in our imagination. Which is inspired by the landscape more than one might think, because first of all, it is landscape itself. Leopardi rightly says, when he claims that, especially in childhood, we are all somewhat a vibration of relationality with places. Not in vain have the landscape and places made a nest and a myth, right from the very beginnings, for religious rites and for firing the imagination in fairy tales, poetry, figurative arts and music. Not in vain do the landscape and the place still constitute the first and essential challenges for architecture and town planning.