“Mother Earth births

everything for us. Father

Sky carries the water

and oxygen for us to breathe.

Grandfather Sun warms

the planet, warms our body,

gives us light so we can see,

raises the food that the

Mother births and raises

most of our relations,

all our plants and trees.

Grandmother Moon moves

the water and gives us the

woman-time and our birthing”

Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison, Aboriginal elder of the Yuin people “My People’s Dreaming“

Today I stood on the grass under the trees in the Botanic Gardens of Sydney, the traditional land of the Cadigal people, with Glenn Murcutt, Aboriginal Elder Uncle Max Dulumunmun Harrison, Peter Stutchbury, and a gathering of people for the launch of Uncle Max’s book ‘My People’s Dreaming – an Aboriginal Elder speaks on life, land, spirit and forgiveness’1 by the Governor of the State New South Wales, Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir. The event took place with glimpses of Utzon’s Opera House through the tree-tops and with the tall buildings of Harry Seidler, Renzo Piano and many others looking down on us from the city centre across Macquarie Street. Richard Leplastrier was there with us as well, in spirit, although he was in Japan on his way to Denmark. Glenn, Uncle Max, Peter and Richard, with Professor Brit Andresen from Norway and Queensland, have become a close family, privileged with each other’s company and engaged in, one could say, spreading a teaching of thought and action that is commonly rooted in the accumulated wisdom of these two great men, Glenn and Max, now our Elders.

Gathered in the Botanic Gardens we were surrounded by threads and symbols, which give several cues for a short essay on the life of and works of Glenn Murcutt and his place in the trajectory of Australian architecture. Glenn speaks often botanically, as he did in his Pritzker Prize acceptance speech, his knowledge and observation of the natural environment is extraordinary. To walk over a landscape with Glenn and to hear him identify and discuss the plant species with their botanical names, is to have revealed insights into geology, rainfall, water flow, wind direction, solar access, bushfire threats, the movements of the seasons, wildlife, scents, so it is that his buildings are, first, ‘grounded’ on the reading of the land, of the landscape. Walking with Uncle Max over this same ground is another, parallel and complementary journey. He will speak of the hillside and the trees as his family relations, of the traditions and journeys of his ancestors, of reading the land, of spirit lines, of totems, of sacred places and of the landscape as a source of food – “When I take people out in the bush, I ask them to look around and tell me what they see. They say, ‘We just see the bush, Uncle. What do you see?’.

I say, ‘I see a supermarket!’”

It was not until the late 1970’s that Glenn developed an interest in the culture of the Aboriginal people of Australia and from 1983 this culture fired his imagination. Philip Drew’s book ‘Leaves of Iron’2 published in 1985 articulated an underpinning to Glenn’s work in this regard. Since then he has become an ardent collector of Aboriginal art, and has made several privileged trips to areas of Australia with rich indigenous traditions. He has drawn from Aboriginal culture, respectful strategies for oblique approach and entry to buildings, adopted, for instance, in the Simpson-Lee House (1988-94) and, then, he had the opportunity to design the house for Aboriginal leader Banduk Marika and her partner Mark Alderton, in the far north tropics of the Northern Territory.

Down through the Botanic Gardens, on Benelong Point, jutting into Sydney Harbour, Utzon’s great Opera House is a reminder of Glenn’s great respect for, and love of, Scandinavia and its architecture, his inspirations drawn from Utzon, from Aalto, Asplund, Lewerentz on his early and later travels to Europe, and personal friendships with such as Juhani Pallasmaa the late Sverre Fehn, that have informed much of his work from the early buildings with Allen and Jack Architects at the University of Newcastle and right through his career to the Boyd Art Centre ‘Riversdale’ and continuing.

His favourite chair is still an Arne Jacobsen designed Fritz Hansen Series 7 on which he sits at work. At the opening of the exhibition of Glenn Murcutt’s drawings and buildings at the Museum of Sydney, just across the road from the Botanic Gardens, in June 2009, (originally shown at the Gallery Ma in Tokyo in 2008)3, I posed the question – “What would be the international perception of Australian architecture, if we had not had Glenn Murcutt?”. Penny Seidler, widow of another great Australian architect Harry Seidler, was not overly impressed.

What I should have said is that Harry Seidler, who came to Australia from Europe and America in 1948, having studied under great men such as Gropius and Breuer, brought World architecture to Australia – whereas Glenn Murcutt, in his time, has brought Australian architecture to the World. Many of the buildings in this Area publication, and the fine photographs by Anthony Browell, were featured in the Sydney exhibition. Something like 25,000 people visited the exhibition of Murcutt’s work over three months, which highlights the interest and affection that the public, and the profession, have in his unique sole practice, his methods of working and his uniquely Australian projects. Not all within Australia are unequivocal. None would question Glenn’s integrity, but some see his work as too comfortable, less than cutting edge, perhaps of the past. I gave a lecture in Mexico some years ago – an overview of Australian architecture – and I cast the scene in two camps – the “Touch this Earth Lightly” (Glenn learned of this now famous Aboriginal saying from his friend Brian Klopper) camp from the east coast, who draw their inspirations from the ground through the soles of their feet, led by Glenn Murcutt and, then, what I called the “Radical Avant-garde”, mostly centred on Melbourne in Victoria, who draw their inspirations through the crowns of their skulls out of the ethersphere, more concerned with international trends, styles and theoretical positions. Glenn says he is not interested in theory, he is interested in doing. He also, as the exhibition of his work emphasised, is committed to the use of the hand to draw and to “discover” as a path of exploration, and is deeply suspicious of the use of computers. “Drawing with a pencil, the hand can discover the solution before the mind can conceive it”.

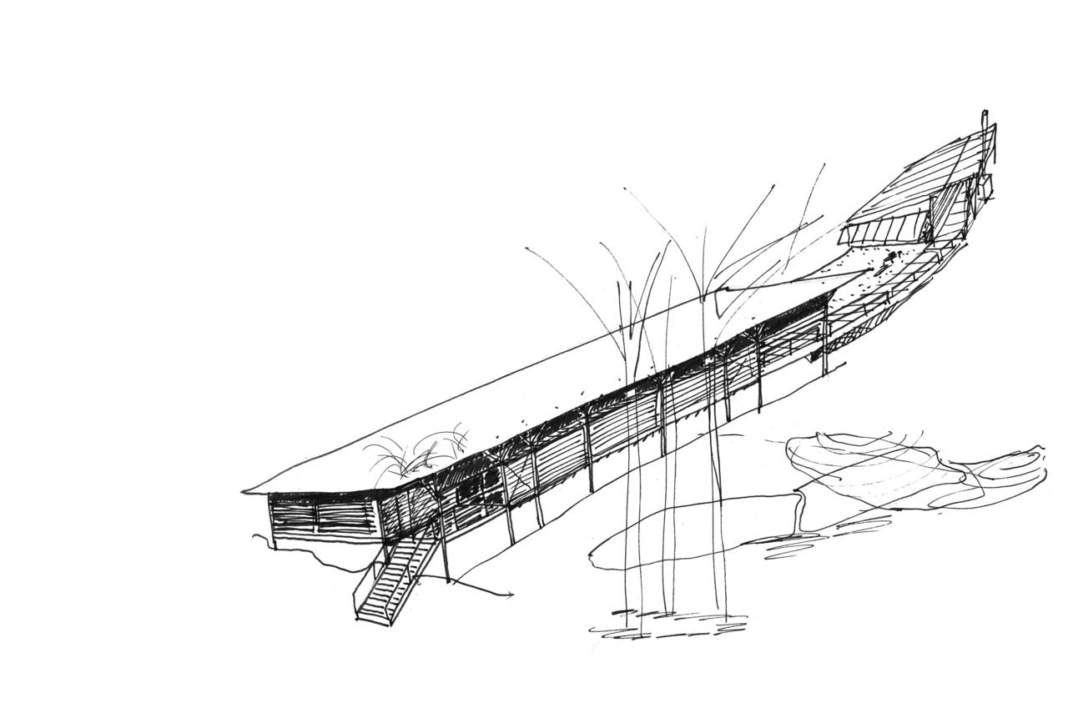

While the works that have mostly brought him to the attention of the World are his houses, he is criticised within Australia for not taking on bigger works, The Boyd Centre ‘Riversdale’ (1996-99 with Wendy Lewin and Reg Lark) and the Borwali Visitor Centre (1992-94 with Troppo) stand out as fine works of public architecture, however some of his finest works are buried in the archive of unbuilt projects, several of which are significant public buildings of larger scale and great interest that, to our great loss, have not been realised.

For example, just a stone’s throw from where we were standing in the Botanic Gardens, the Customs House on Circular Quay for which he and Wendy Lewin did a conversion design (1993), the Alcoholic Rehabilitation Centre near Kempsey (1983-5), the Wollongong Herbarium and Visitor Centre (1986) and the Minerals and Mining Museum, Broken Hill (1987-9 with Reg Lark). It is to be hoped that two current projects, the Opal and Fossil Museum at Lightning Ridge (mostly undergound) and a new Mosque in Victoria, will reach fruition.

Glenn mentioned today that he regretted that the Lady Governor, Professor Marie Bashir, had approached him some years ago to design a house, but was unable to wait in the queue of clients who patiently attend, sometimes for years, to have his services. He has been described as a maverick (a stray animal without a brand!) for his persistence in working alone and without office support, secretary or a mobile phone. This is what makes him so special, and his work so special, his absolute commitment to hand-tailor his buildings to their place, and for the clients, and with full control over all aspects of their design, detailing and production. To do this he works incredibly hard, he still talks, at age 73, of working until 4am, drawing by hand the exquisite working drawings in ink and pencil, at a drawing board, and then driving in the morning several hundred kilometres to meet his clients. On a recent visit with a group of international architects to one of his houses, Glenn was to be found dis-assembling the lock on the front door to effect repairs. At ‘Riversdale’ he can be found repairing leather binding on exit door handles or adjusting the angle of the lights.

Richard Leplastrier and Glenn Murcutt are dear old friends, contemporaries that have taught together since the mid-1970’s.

Françoise Fromonot, in her book ‘Glenn Murcutt – buildings and projects’4 writes about the significance of this friendship, brought to her attention by Rory Spence, an academic in Tasmania, sadly no longer with us. Richard was working on his seminal Palm House on the Northern Beaches of Sydney at the same time as Glenn was working on the Marie Short House near Kempsey. “Leplastrier set the pace with his Palm House by trying out a functional and spatial approach of which traces may be discerned in some of Murcutt’s later work.” Richard worked with Jørn Utzon on several house projects (1964-66) and subsequently studied under Professor Tomoya Masuda in Japan. Hence the symbolism of Richard’s trip at this time to Japan and Denmark, a pilgrimage of homage to HIS Elders. Richard’s Palm House is attributed as ‘built by the architect and his shipwright friends’, and therein lies both a connection with Murcutt, who too sailed boats and built them as a child, and a foundation for both sole practitioners in what could be described as ‘extreme craftsmanship’. As a continuum from Glenn’s well-documented early influences from Mies van der Rohe, his quote from 1959 “God is in the details” exemplifies Glenn’s extraordinary body of work. It is difficult to comprehend the excellence and refinement of the details in the built works without being there and touching them. Glenn speaks about the epiphanal visit he made to the Maison de Verre (1928-31) in Paris in 1973. Chareau and Bijvoet used ingenuous technology, what Professor Tom Heneghan in his essay on Murcutt in ‘The Architecture of Glenn Murcutt’5 says Glenn refers to as ‘contraptions’. The use of standard components to which are applied craft skills is a recurring theme in Murcutt’s work – for instance the signature fireplaces in many of his houses, based on a standard ‘Jetmaster’ firebox encased in a purpose designed and made steel box as receptacle for added thermal mass and wood storage, painted symbolically red. Françoise Fromonot tells how Glenn was fascinated by the relationship between the glass brick façade and the paving in the courtyard at Maison de Verre – spend some time in the big room at ‘Riversdale’ and study the alignment of the ceiling panels, the stuctural grid, the floor and forecourt paving and the door openings and, particularly, study the width of the stiles (the vertical side members) of the large recycled timber glazed sliding doors to the east elevation and note how they are varied in width so that they align with the width of the concrete columns when the doors are closed. To anyone who thinks Glenn’s detailing is old fashioned – just carefully look at the detail of the Murcutt-Lewin House and Studio, particularly the frameless glass window to the main living area and the profile and detail of the amazing roof windows to the upstairs bedrooms. Françoise Fromonot devotes a section in her book to a Murcutt legacy – those who have drawn from his body of work. Peter Stutchbury, of the group standing in the Botanic Gardens this sunny October day, carries this mantle, having studied under and taught with Glenn and Richard, now an award winning architect in his own right being widely published internationally. It was he who introduced us all to Uncle Max Dulumunmun and it is he who has pushed the boundaries further in the application of the dissolution of inside and out, of the folding away of external walls, of exquisite detailing, of ‘gadgetry’ often associated with innovative environmental strategies. I suggest that maybe some ‘traces of Stutchbury may be discerned in Murcutt’s later work!’, for instance the sliding doors and screens that project outside the main building envelope, found in Peter’s Verandah House at Bayview (2000-04) and in his Deepwater Woolshed (2001-03), can be found in at the north-east end of Glenn’s Walsh House in Kangaroo Valley (2001-05). Glenn likes to recount that he failed ‘Sunshine and Shade’ when at University, but one of his primary reference books still today is ‘Sunshine and Shade in Australasia’ by Ralph Philips (1951)6 written long before issues of environmental sustainability gained the World’s attention, and he can now recite solar angles and orientations for different times of the year and different parts of Australia, by memory. Another epiphanal moment for Glenn was, apparently, when he met Craig Ellwood in California in 1973 and interrogated him about the lack of sun control and insulation in the predominantly glass Kubly House in Pasadena (1964-65), to be told “why, we air-condition the buildings”. Since that time Glenn has been committed to designing buildings in all the varied climatic conditions of Australia, without air conditioning.

His design sketches in plan always, first, identify the orientation and, in section, the solar angles in winter and summer. His long thin houses afford good cross ventilation for hot summers and good solar access for cool winters. He ridicules standards that require consistent thermal conditions and is famous for saying – “if you’re cold, put a sweater on!” Like his exquisite detailing, many of his environmental ‘gadgets’ cannot easily be understood from photographs. Close scrutiny will reveal his ubiquitous screening of wall and roof glass from sunlight with external aluminium louvres, hinged ventilation flaps that open at window sills behind desks, kitchen benches and above bed heads and copiously detailed rainwater downpipes feeding water storage tanks.

At ‘Riversdale’, on arrival, study the subtlety of the siting in relationship to the existing cottages and the ‘aspect’ as the building reveals itself, study the relationship of the building to Arthur Boyd’s hill and how the roof geometry lifts up to address the ‘prospect’. From the photographs of the Walsh House in Kangaroo Valley, note the axis of the house and its ‘prospect’ towards the distant rocky hill and the shallow ponds there, and at the Simpson-Lee House, that pick up the pattern of the breezes. Glenn often quotes Luis Barragán as saying “Any house that is built without serenity, is a mistake”. On World Architecture Day, 5 October 2009, Glenn appeared in conversation at the Sydney Opera House with eminent Australian author David Malouf. They are approximately contemporaries, born in the 1930’s, and hold a mutual admiration for each other. Malouf talked of his early memories of the physical detail of the house he grew up in Brisbane, recounted in his memoir 12 Edmonstone Street, and of his father, just as Glenn talks of his childhood home and the dominating influence his father has had on his life. Malouf has written an eloquent essay on Murcutt in a large folio publication ‘Glenn Murcutt’ published by 01 Editions7 and speaks at the end of “tough lyric grace” as a balance between hard intellect and sensuous indulgence.

“The toughness in his case lies in his down-to-earth commitment to conditions, use, austerity of means, his refusal to make any gesture that cannot be justified as ecologically necessary. His lyricism springs from the same source, though what we might call it, under this aspect, is not ecology but, more romantically, Nature: a response, directly through the senses, to light, movement, line, curve, angle and all the natural phenomena these elements form, refer back to and evoke. This lyric play is what constitutes the rigorous beauty of Murcutt’s work.”

One of Uncle Max Dulumunmun’s penetrating sayings is “To keep it, we must give it away”, referring to need for the Elders to reveal their knowledge and culture to younger generations, to be generous in the giving, to commit time to the giving. Glenn Murcutt has devoted a huge proportion of his life over recent years to ‘give away’ his knowledge and experience and he does this with great humility – an unwilling celebrity. He has travelled extensively to lecture and teach around the world, and it is testament to the value perceived in his teaching by young, and not so young, architects from around the world, who travel each year to Australia to attend the now annual Glenn Murcutt International Architecture Master Class, held at his Boyd Art Centre ‘Riversdale’, that participants from forty-six nations have participated since its inception in 2001.

“The future lies with our younger architects and with our understanding of the conservation and the ecology of our planet...

I think that the landscape is really the appropriate common thing to all of us... I am talking about the conservation of materials, the conservation of land, the keeping of old growth forests, the understanding of how we might be able to find a sustainable building.” (Glenn Murcutt)

Lindsay Johnston is Director of the Architecture Foundation Australia and former Dean of Architecture and Design at the University of Newcastle, Australia. He is convener of the annual Glenn Murcutt International Architecture Master Class and was curator of the Sydney exhibition ‘Glenn Murcutt – Architecture for Place’ (www.ozetecture.org).