millenium stad

text by Antonello Boschi

At times, reading a novel or watching a film can be the best guides to a city. The idea, for instance, that we got of Stockholm through 1960s’ cinema: on one hand, Gian Luigi Polidoro’s comedy “Il diavolo“, which once again unveiled the myth of Nordic women seen with the eyes of the average Italian par excellence, Alberto Sordi. The dialogues and above all silences between Amedeo Ferretti and the girl in the hotel with a view of the entire Scandinavian night, tell us of an uninhibited city, but where emotions remain forever private. Impressions which instead become public in the façades of the Hötorget buildings where, the complex built by Helldén, Markelius, Tengbom, Lallerstedt and Backström & Renius, thanks to an installation by artist Erik Krikortz, is transformed into an enormous urban kaleidoscope, in which each citizen can express his mood by logging on to the website emotionalcities and answering the simple question “how do you feel today?” through means of a colour scale. On the other hand, a Hitchcockian film of 1963 directed by Mark Robson, The Prize, unveils a both elegant and mysterious city where Paul Newman and Elke Sommer endeavour to thwart an international conspiracy in the shadow of the Nobel prize ceremony.

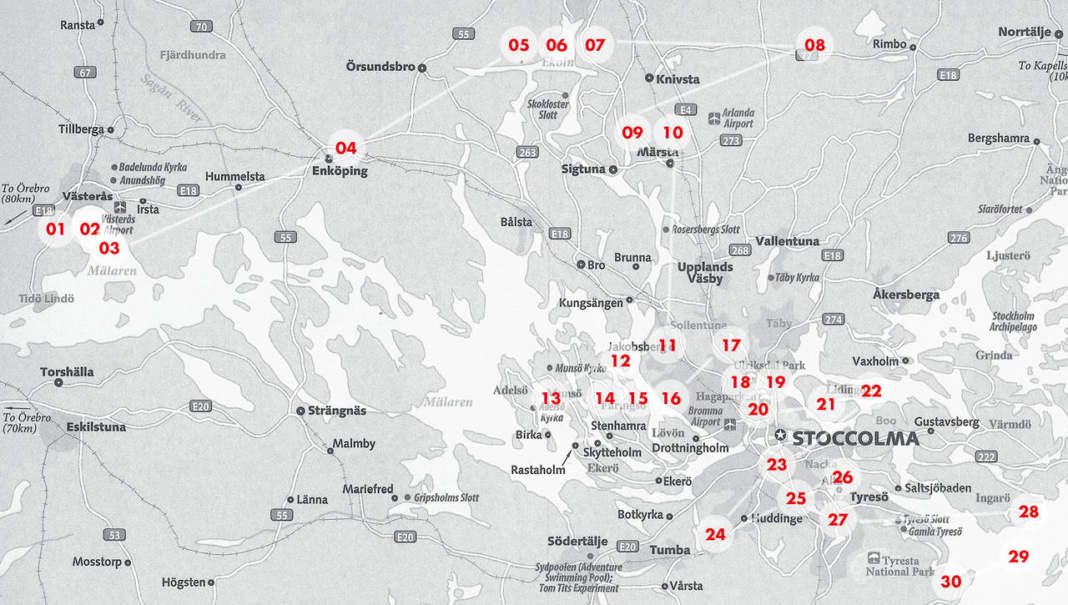

These are the years in which the city – or better the entire metropolitan area – in just two decades multiplies its population from 220,000 to 1,400,000 inhabitants in 1980, subjected to conflicting housing policies: first, the programme for one million new residences, subsequently steering building toward smaller, more measured forms of housing. Dilatations and contractions, accelerations and sudden halts which have alternated around the turn of the millennium, first with the financial crisis of the early 1990s and subsequently with the global recession of the end of 2008. Speculative pressure oriented above all towards the property market of offices, against which the government has put up strong resistance through instruments like the action programme on architectural policy, but also stimulating interest in architecture by promoting appointed places such as the Moderna Museet, inaugurated in 1998, or by holding international competitions, now a praxis for assigning important public buildings. If we add to this the young population’s shifting from Norrland to Götaland, and generally from rural areas to the city, it is easy to understand how social conflicts were just round the corner. A faithful mirror of these contrasts, the pages of Stieg Larsson’s trilogy which reveal an insensitive, harsh and corrupt capital, already glimpsed in the photograms of “Racconti di Stoccolma“4, so far from that idyllic, sweetened image of the Swedish model, of socialism seduced by capitalism, of that word lagom, which indicates a kind of middle course between things.

la città tra i ponti

text by Andrea Bulleri

At the end of the Saltsjönfiord, the Baltic meets Lake Mälaren, but with difficulty: the water must conquer its space amongst a myriad of islands, before becoming freshwater in proximity of the lake basin. The landscape predominates and transforms, following the changeable, capricious channel of the water’s physical states. The limits extend, become uncertain – especially during the harsh winters – and the elements merge: the limits between land, water and sky become faint and everything seems possible1. And that’s when it happens! In the most improbable of places, where human presence appears banned, historical conditions for the genesis of a town get under way. A founder with mythical features, Birger, the Jarl of Bjälbo, decided to create a city on the pre-existing 11th-century fishing village, that was able to guarantee protection of the hinterland and permit expansion of commercial traffic towards European ports. In the 13th century, in just a few years a new settlement was built around the castle of Tre Kronor, on the little island of Gamla Stan, regulating the water course with timber weirs between Stadsholmen and Riddarholmen: Stockholm, the “city among the bridges”, developed as a port of exportation of copper and iron originating from the region of Bergslagen, becoming one of the chief members of the Hanseatic League. Its very constitution, according to Birger Jarl’s orientation, was to determine – given the favourable logistic location, a barycentre in relation to the dominions of Gotar and Svear – the definitive process of aggregation and consolidation of the Swedish state (Sverige from the ancient Svear Rike: kingdom of Svear). Within a short lapse of time, an area without any real centre of reference, assumed a leading role in the Scandinavian area and such compactness that it even tried to expand onto Russian soil, an attempt thwarted by Aleksandr Nevskij at the mouth of the river Never in 1240. Over subsequent centuries, the rapid genesis process was followed by slow consolidation, until the urban revival of the 17th century, celebrated by the exuberant Baroque style introduced by the Tessin: grandiose presences, functional for representing the new Swedish capital, yet not invasive compared with the original Medieval architecture. The very equilibrium between the countryside and urban system, which has orchestrated the gradual expansion of towns to the point of covering the current 14 islands, has avoided the temptation to radically renew the metropolitan area in the 1900s, according to a radical vision of modern town-planning. In fact for the crumbling Gamla Stan, the heart of the town’s history, there had been a plan for its complete demolition and a new, more functional road system2 to make for a modern metropolis: only insistent protests made by eminent personages such as August Strindberg and Carl Larsson, led to the suspension and subsequent abandonment of the projects. The area was definitively placed under protection during the 1960s. Today, the old town is one of the largest, best preserved medieval historical centres in Europe.