Manuel Gausa

From public space to relational space: we have made the transition from a monumentalistic traditional concept – representative or symbolic – to a more active, operative concept. We have abandoned the old public space for a rational one. An authentically collective space, open to use, enjoyment, stimuli, surprise: to activity. A space where the dynamic is not pre-defined, where active and passive users – activating players – are interchangeable. In other words, not a space featuring “urban furniture” based on the subtle figurative evocation of ancient historical paradigms (the Italian – or we may say Mediterranean – piazza, the rambla, the boulevard, the garden etc.) as aesthetic and aesthetizing aspiration of a civic space, between domestic and neo-micro-monumental, fixed and stabilized: painstakingly finished and planned with an eye to composition. In other words, not a space for a precise and as such finite recreation (purist and/or autistic aesthetics aimed at the enjoyment of occasional rebels-vandals) but a space of new landscapes – or landscapes of landscapes – which rely on more open approaches, sensitive to change and interaction, to more open approaches: generators of energy and activity. Spaces that are not only based on formal designs, but also on informal relations. Not on the civic model, but on hybrid situations. Not so much domestic salons as active landscapes – multi-programmatic – where the manipulation of the land is combined with a plastic, direct, expressive, changeable manifestation, open to the appearance of installations (permanent or ephemeral) for free time, sport, culture, gastronomy, consumption, socializing; in short, the projection of the citizen.

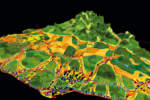

But also with a new concept of the conceived – and developed – uses “in negative” or in virtual “folds” of the ground: new “dense topographies” of activity. In any case, new environments appreciative of the incorporation of auxiliary constructions, of natural and artificial vegetation, of more casual, expressive – and economic – solutions, conceived on the basis of alternative “recyclable” materials, but also on the saving of energy and its recovery in the form of illumination, electricity, irrigation, etc. A relational space which is not just public, not just “regenerating” but also playful; operative rather than representative, conceived for strolling and contemplating but also for use and enjoyment, or for a true social exchange. Basically, a space that is inspiring rather than “elegant”. At one time we coined the expression lands in lands: “operational landscapes” on “host landscapes”.

It enabled us to reflect on the surpassing of the old concepts which had characterized actions on the landscape based on the traditional “figure-background” – “building figure against background” hierarchy, and the replacement of these concepts with new interpretations that were more open to a merger of the edges, to a dissolution of the borderlines (as in those fields of pixels used in digital representation where the silhouette which is gradually zoomed in ends up by being diluted into more abstract and interconnected plots). On an architectural scale this intersection could also be conceived on the basis of possible encounters and operative “tales”, not just programmatic but also “categorical”, capable of transforming the existing conditions of a place into new movements of relief, virtual “nature-buildings” characterized by a hybrid configuration. In fact, it would not be a matter of being “diluted” in (or before) nature but to interact with it, also favouring “other” types of nature(s). Topographic and topological. The force of the term “landscape” and its rapid and diffused inclusion in our recent conceptual baggage is rooted, precisely – rather than in its manifestation as mere scenario – in the fact that it is an operational instrument capable of favouring the delineation of new open yet structuring systems.

This transferral of the background of the scenario to the centre of action proves ever harder to circumscribe to the concrete context of a specific or complementary activity – i.e. “landscapism” – with hazy and general environmental connotations, unless it also involves the authentically architectural dimensions. The scope of a present-day work on the idea of landscape must be identified precisely in its ability to capture new dimensions, to go beyond the limits, to blur the silhouettes and to give a new outline to the familiar profiles of what we previously considered to be town planning and (or) architecture. As we have already observed, this dynamic is not foreign to the idea of considering the void as “architectural material” of the first order, not so much by virtue of its possible “natural” value as for its fundamental abstract and diffused component, which goes beyond the predomination of the form (as mentioned, this ambiguous quality of the “vacant”, “negative” space, which owes its form more to the “absences” than to the “presences”). An “architecture of the void” may therefore assert itself in resonance with the qualities of a “landscape-free space” exploited precisely through its peculiar spatial manifestations, as “field” of open forces. An architecture made of “presences-absences” capable of being built on foundations made from a – paradoxical – combination between densification and disappearance, and where the surfaces, horizons, meetings of sky and earth are forcefully manifest. Just like the borders separating the city from the ancient territories beyond its walls have been dissolved, the architectural plan may see its profiles blurred into new “hybrid geographies of transition”.

Topography rather than volume.

Artificial landscape rather than host landscape. Yet again. Untreated, functional surfaces rather than free and receptive ones. New, dense surfaces rather than possible extended ones.

The project which centres on the surface will therefore be understood as a work on an “architecturalized” void. A “vide façonné” in which the design is not based on the configuration of masses erected in height – architecture as “building” – but on the reorganization of its horizontal dimensions: peaks, dunes, trenches, furrows, folds etc., will be understood as topomorphic manifestations of a possible artificial geography that is not very distant – in terms of its spatial image – from the more natural one. Reliefs and level surfaces, folds and cuts “are impressed” in a new way on the territory, mineral landscapes where movements and flows are organized “below the surface” and “inside the surface”, in chiselled surfaces that are (almost) level with the ground. It is therefore not a matter of continuing to create pretty “volumes of light”, but “hybrid landscapes of sky”. Hybrid enclaves capable of autonomously generating their own energy.

Fields within other fields.

Lands in lands.

We define devices “operational topographies” (Quaderns 220) when they are conceived as, on the basis of, strategic movements of folds in the territory. These movements define platforms and (or) enclaves of an almost geographic nature developed as “programmatic revesas” (using the term revesa in its dual meaning of “current or movement of flow and reflux deriving from a principal source” and of “astuteness in acting”): that is to say functional “reliefs” or “surfaces” whose condition of “operating landscapes” is intensified, both as smooth or extended (dynamic grounds) or as extruded surfaces (localized reliefs). In both cases it is a matter of virtual manipulated “landscapes” where the “landscape” is defined as “background”, as “scenario” or as “construction”, that is to say, “landscapes within other landscapes”. The “surfaces” are the result of a pursuit of “multilayer superimposition”, a context within which we find many of the architectures which have played an important role in landscapes in the new century: the works of Actar Arquitectura of Graz Maribor (2000) and Bruxelles Change (2003) or the famous memorial of Chi chi (2005), the well-known memorial for Oscar Peterson (Soweto) by François Roche (1997) or the Terminal of Yokohama by FOA (1996-2003) and the previous works of OMA but also the multimedia studio of Kazuyo Sejima in Gizo (1996) represent some of the first graphic intuitions of this potential.

The “reliefs” are the result of a desire for localized “accentuation” and in this sense it is to the point to mention both the famous project for the auditorium of Pamplona by Eduardo Arroyo (1998) and the “mountains” designed by Vicente Guallart for Denia (2003) or by MVRDV in Stockholm (2000), both of whom are indebted to projects as that by OMA in Agadir (1990) or the one of Jussieu (1992)…Whether it is a matter of level extruded surfaces – reliefs or enclaves – or chiselled ones – grounds and platforms – these topographies will in every case come to form new “geographies” above the territory. Built geographies, rather than architectures.

Interview June 16 2010.

Wes Jones

To understand the proportion that there can be an un-volumetric architecture, it is necessary to belive that architecture may be divided away from a simple limiting congruency with the necessarily spatial, that is, with buildings. This possibility may noticed today for two reasons: first, because technology has leapfrogged beyond the limits that architecture traditionally helped to establish, and gained a vantage, point from which to see those limits as provisional rather than absolute. And second: because a generation of architects has come of age that were raised with this viewpoint “outside the discipline”. The consideration of architecture from an un-volumetric perspective might be an important first step toward strategizing architecture’s survival in a future where these traditional underpinnings are missing or uncertain…We can consider the term “the architectural” (rather than simply “architecture”) might be advanced to refer positively to a general case of architecture-ness, one not ferred to specific, isolated products that might be prompted by a greater variety of object-stimuli, or variety of stimuli within a single object. Thus, not specific instances of architecture, invariably buildings, but a broad, and exportable sense of the architectural, that could be applied to or explain a wider range of experience.

From Aldo Aymonino, Valerio Paolo Mosco, ”Contemporary Public Space. Un-Volumetric Architecture”, Skira, 2006.

Ilhyun Kim

The architectural objects of the public space, the un-volumetric architectures, underline the same ontological rules of futurist and minimal sculpture. The reason for these objects travels substantially along two channels: on one hand the permanence of the same, on the other its mask, its aspects “for the occasion”. Most times the mask prevail over the more intimate reasons and the reasons of the objects are expressed as signs and codes of an instant, as pure communication. It was on these principles that Christo, Matta Clark and Whiteread worked, on how the involvement of the observer could be exported to the architectural dimension and linked to the concept of public space.

The notion of un-volumetric architecture not only proposes a critical category regarding the current multi-valences of contemporary architectural objects and interventions, but even attempt to retrace an alternative epistemological basis for the theories and history of architecture…an object matters if architecture embraces the entire atmosphere in which human activities are engaged.

From Aldo Aymonino, Valerio Paolo Mosco, ”Contemporary Public Space. Un-Volumetric Architecture”, Skira, 2006.

Kengo Kuma

I want “erase” architecture. This is how I’ve felt; this is how I will continue to feel…architecture will be kept dissembled. We shall have an age of architecture without cubic volume. The time is moving forward rapidly, and the way architecture needs to be is also changing. In my sense, public space (or architecture), is a place to inspire communication between people. Indeed architecture is changing so. Near my office in Tokyo there is a cemetery called Aoyama Bochi, which is popular and known for cherry blossoms surrounding it. In spring, people get together there to celebrate the blooming of the cherry trees and have nice time drinking and eating under the trees. These cherry trees are exactly my image of ‘space-less’ architecture, which I myself also aim at.

Interview June 10 2010.

Luca Molinari

Public space is today assuming a new fundamental strategic dimension for the future of the metropolis. The profound metamorphosis of the social corpus carries with it new desires, ways and uses of the collective space, which becomes carrier of a demand for new spatial realities and visions. In a dimension of coexistence of social, racial, cultural and religious differences, rethinking the public space today means to deal with an idea of collective place as mediator of potential conflicts and, at the same time, as place of community life. In a condition of profound structural crisis experienced by the Western society and from a viewpoint of a profound revision of metropolitan welfare, the design of the public space will become increasingly decisive and strategic.

All forms of design of the public space which consciously play with the absence of territorial consumption and new resources represent a political and cultural choice that is not only necessary but also economically relevant. In these cases the design of the collective space with “zero cubic volume” also becomes a “didactic” instrument for creating a social awareness and building a consciousness that is vital for the life of our metropolises. I think of all the squares in central and southern Italy, along the Apennine ridge, where a view of the open landscape represents the “fourth side”; I remember the hanging garden of the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, designed by Laurana with the complicity of Francesco di Giorgio and the way in which Giancarlo De Carlo, five centuries later, has evoked it in his University Colleges and city venues. I have been very impressed by the projects for a cogeneration station by Modus on the outskirts of Bressanone, of which roof has become the favourite site of the skater community, and the roof cum basket field of the university bar designed by NL architects in Utrecht. The centripetal void of San Pietro in Montorio in Rome by Bramante, but also the archaic and sacral periurban void of the cemetery of Igualada designed by Enric Miralles. However, the void has always been a conscious material of architecture, and we must perforce supplement this very ancient art with the necessity of avoiding to consume more territory and, at the same time, to use the few remaining resources in a conscious and experimental way.

Interview June 14 2010.

Juan Purcell

Cooperativa Amereida come about, therefore, as a public group and we have the public as our destiny. The destiny of being Latins, which does not means the power of the public, but the public as uneliminable human condition. Faithful to this vision, in the seventies we started the Ciudad Abierta project, inaugurated with the construction of agoras, open-air spaces where the words flows and decides on the public affairs of the city. Subsequently we built the guesthouses, the music room to come together, the chapel, the cemetery and other buildings. All these works came about as poetic experience. This experience made us understand that the relationship with the terrain must be light… their location is decided upon each time by a poetic act that involves understanding, first of all the understanding of the destiny of the work in relation to its natural location, discovering and proclaiming the positivity of lightness.

The works in Ciudad Abierta give life to an inside space lived in the open air, in a natural environment in which architecture acquires the dimension of lightness and availability; all of this through a lived architectural experience. A type of experience that combines the lightness of poetry, of what comes from within, with the availability of nature, which is found outside. This is our interpretation of un-volumetric architecture in the Ciudad Abierta.

From Aldo Aymonino, Valerio Paolo Mosco, ”Contemporary Public Space. Un-Volumetric Architecture”, Skira, 2006.

Denise Scott Brown

Reyner Banham suggested that primitive living arrangements could be non-volumetric and linked this to the tempering of environment in our day by mechanical systems. At the other end of the spectrum was the cave and between these, we might insert Laugier-like structures…some non volumetric categories (canopies, skin structures, and technological and micro-structure) seem to originate conceptually with the skins and branches of primitive hut. They go back, too, to early Modern architects’s fascination with Costructivism and transparency, and to 1950’s experiments with thin-slab of engineers. Despite our scepticism about lightweight structures, the concept of non-volumetric architecture became important to us through our studies of Las Vegas in the 1960’s. This urbanism – so different from Las Vegas today – was dominated not by buildings, but by sign. In a general way, desert buildings face the quandary that they are small relative to the vast space around them. A solution as old as Karnak was to project lines across the vastness: sightlines, defined by points of various kinds, set in the desert. At Karnak the points were rows of crouched lions. They helped to modulate the approach and direct the view to relatively small Temple of Khons. In the 1960’s Las Vegas followed this example. The scale of the Mojave desert and of the desert of parked park of the Strip swamped even the largest casinos. Their walls could not define the boundaries of the street. As at Karnak, space had to be modulated by vistas projected across it. The “points” that marked the vistas were signs, large and small. Their walls could not define the boundaries of the street. As at Karnak, space had to be modulated by vistas projected across it. The “points” that marked the vistas were signs, large and small. Their function was to communicate with people driving and riding, giving them messages about casino hotels and others establishments set back from the Strip. On the 1960’s Las Vegas Strip the signs were much more prominent than buildings. They were what was seen first. Their high readers guided visitors to the buildings, then their low readers gave information on event to be found inside. Approaching Las Vegas, one understood (as in any city) that density was increasing as one neared the center. But here the perception had to do not with the larger size and closer spacing of buildings, but with a greater intensity in the rhythm of communication. This was a non-spatial, non-volumetric form of definition, far form the traditional city. Planned as carefully as scientific equipment, these neon giants were visible from the air. They inspired our slogan: “symbol in space before form in space”. And in the process of making and advertising private buildings, they defined the public identity, formal and symbolic of the Strip and, to a considerable extent, of the city.

By enlarging archirtecture’s scope and conceptual categories, by accepting that our field is involved in both more and less than the making of space, this book can bring new dimensions and added richness to what we do.

From Aldo Aymonino, Valerio Paolo Mosco, ”Contemporary Public Space. Un-Volumetric Architecture”, Skira, 2006.

Vittorio Sermonti

I think about public space not so much through concepts as through mental images. I come to think of an aphorism by Hugo von Hofmannsthal: “the depth must be hidden on the surface”, which helps us understand the phenomenology of contemporary public spaces and architecture with zero cubic volume, understood as a succession of countless horizontal plots. I also come to think of Borges who dreamed of a map as big as the world: a mental image which suggests the idea of a world that is completely accessible. A concept prefigured by Dante, in the 27th canto of the Inferno, the one on Guido da Montefeltro, in which the description of Romagna is entrusted to a concrete, physical cartographic symbolism which is elevated to poetic narration.

The public space is therefore a tale whose nature is inseparable from its narration. There are those who have interpreted the Divine Comedy as a building, or rather as a cathedral, a prescriptive construction (a volume) perfectly retraceable to laws of proportion and symmetry. As to me, I interpret the Divine Comedy in a different way: not volumetric, as a fluid, continuously flowing tale: a story which has the character of life, and not that of the necropolis, in which the predominance of the symbol on reality is evident. Also Baudelaire has seen Paris, its physical reality and public spaces, in their symbolic meaning, as a complex sequence of horizontal plots and correlated mental associations. The city described by Baudelaire is very different from that told, for instance, by Victor Hugo: it is no longer made of stone, it is no longer volume and representative spaces. It is already the city of today, with its public spaces. I see contemporary public spaces as a tale from below, which seems to be casual and unpredictable in its expressions, but which in actual fact implies the laws of the consumer society. The result is what I may define as “aleatory decorum”, ephemeral, vital, but sometimes noisy, chaotic, graceless and unseemly. In the worst cases calls to my mind the image of the Turks encamped at the gates of Vienna.

Interview June 17 2010.

James Wines

I have written repeatedly on the subject of public space since the 1970’s and my books (‘De-architecture’ of 1986 and ‘Green Architecture’ of 2000) make extensive references to the issue of ‘not seen’ (or invisible) factors in the public domain. As a writer and designer, I have continuously credited these elements because they engage participants on a social and psychological level that is often outside the realm of conventional formalist design. In fact, Modernist and Constructivist influenced traditions have frequently perpetrated some of the most aggressively intrusive, opaquely physical, environmentally irresponsible and sociologically oppressive public spaces in history. Since I have covered the topic so extensively over the years, I have tried to answer Area’s immediate questions; but also include quotations from other texts that cover the ‘zero volume’ subject from different perspectives. Duchamp referred to his most important work as ‘non-retinal,’ even though you could obviously ‘see’ his objects optically. The point he was making is that truly conceptual ideas affect the viewers’ attitudes toward a situation – and this would include public space – based on viewers’ social/psychological/aesthetic response. In other words, the physical existence of certain enclosures and/or open spaces are not necessarily significant as a result of their identifiable physicality; but, rather, because of ‘what they make you think about.’ Area publication’s notion of ‘spaceless architecture’ (at least as I see it) should be much more concerned with how well the aesthetic ingredients of a public space tap into the spectators’ subliminal associations with their environment. Again, like Duchamp’s achievement, the goal is to change people’s minds about something, rather than reinforce what they already know. As Austrian architect Frederick Kiesler once wisely observed; “No object, of nature or of art, exists without environment. As a matter of fact the object itself can expand to a degree where it becomes its own environment.” From a purely environmental and practical viewpoint, underground architecture has obvious advantages in being easier to heat and cool, less physically aggressive in the cityscape and more ecologically responsible. It also provides green roof opportunities and more amenable space devoted to people’s outdoor pleasures. Viewed from a green standpoint – in addition to the merits of troglodyte lifestyle – this kind of construction offers the potential for widespread urban agriculture, which will be essential for city survival in the future. As global warming and air pollution increasingly threaten human health, it will become expedient to limit the long distance transport of food and hard goods – especially if they can be produced locally. Olmsted’s Central Park in New York City. Tivoli Gardens in Italy, Michaelangelo’s Campidoglio in Rome – there are many; sometimes because of their impact on participants, sometimes because of the ecological factors, sometimes because of pure, un-designed idiosyncrasy.

Interview June 14 2010.

There are a number of bothersome questions related to the sources of imagery in contemporary architecture. For example, why are the most sophisticated mechanisms of the cybernetic and environmental era – in particular, computer aided design and greater knowledge of ecological phenomena – used primarily to describe buildings that are stylistically rooted in the early Machine Age? Why, instead, aren’t electronic communications and nature’s processes utilized as inspirational resources for a new visual language? Part of the answer lies in the fact that 1920’s Russian Constructivist architects did not have the luxury of software to articulate their complex formal innovations; so, as a result of architects’ style-scavenging tendencies, they feel obligated to finish the job. Still, it seems oddly regressive to resurrect ideas from the 1920’s, simply because they can be built today. And finally, why have so few architects made the obvious conceptual and aesthetic connections between the integrated systems of the Internet and their ecological parallels in nature? These questions point to the need for a visionary, “eco-digital” based imagery in the building arts. By incorporating ideas from both informational and ecological sources, it suggests new design concepts that echo the mutable/evolutionary changes found in nature and the fluid/interactive flow of data through electronic communications. In spirit, this seems to indicate something more like trying to capture the intangibility of the wind passing through the trees than expressing the cumbersome mechanics of construction technology. It seems more like the quest for an invisible or virtual architecture, as opposed to celebrating the weight and density of industrial materials.

Mundaneum Conference Papers, San Jose, Costa Rica, 2009.

Invisible architecture refers to a symbiotic relationship between buildings, communications systems, psychology of situation, and a concern for protecting the natural environment. This term also proposes that contemporary architects’ absorption of ideas from context can be seen as a far more progressive goal than the traditional emphasis on “object thinking.” This alternative proposes much less emphasis on sculptural form, exotic materials, and convoluted construction technology. Earth-centric design philosophies today, which were once seen as marginal or irrelevant, are rapidly becoming the progenitors of a new conceptual forefront and the basis for a declining interest in the conventional celebration of physical mass in architecture.

From Aldo Aymonino, Valerio Paolo Mosco, ”Contemporary Public Space. Un-Volumetric Architecture”, Skira, 2006.

In this new millennium, architecture has one primary mission – to progress from ego-centric to eco-centric. This evolution refers to a mental state of transference where the habitual notions of an insulated psyche (detached from ecological awareness) are exchanged for the re-awakening of an expansive sense of oneness with nature.

From “Green Architecture“, Taschen Verlag, 2000.

De-architecture is a way of dissecting, shattering, dissolving, inverting and transforming certain fixed prejudices about buildings, in the interest of discovering revelations among the fragments.

From “De-architecture“, Rizzoli International, 1987.

The imagery that a building generates as an extension of its own functions or formal relationships is never as interesting as the ideas it can absorb from the outside. An edifice should be like an environmental sponge, soaking up the most interesting fragments of social and psychological information from its context. In this way, a structure can be seen as a “filtering zone” – as the nucleus of an assimilative process – which can transform the entire definition of architecture into a new form of public art.

From “Green Architecture“, Taschen Verlag, 2000.

A successful work of public art today should not be treated as an object sitting in the environment; rather, it should be interpreted as the environment. From this perspective, art can have an integrative role in the urban/suburban context. It can absorb its communicative content from the surroundings. It can invert, transform, comment on, and question the meaning of all those ubiquitous design conventions associated with architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design. This calls for a new kind of “ambient sensibility” on the part of the artist – meaning a much more inclusive concept of public art.

From Public Art Review ‘Integrative Thinking’ (essay) – Fall/winter edition, 2008.

Public art, architecture, landscape, and urban space can only become fully integrated when their academic definitions have been challenged, their distinctions as separate entities have been discarded, and it finally becomes difficult to determine where one art form begins and the other ends.

From Public Art Review ‘Integrative Thinking’ (essay) – Fall/winter edition, 2008.

SITE treats the design of public space as if it were a living ambience. In fact, one of our primary motivations for creating environments is to include people as intrinsic ‘physical elements’ in the design process – almost as though they were actors on a performance stage. In this way, we show our commitment to “prosthetic architecture,” where the occupants are seen to be as much a part of the construction process as masonry, glass, steel and landscape. Unlike many architects – who, for example, exclude people when photographing their buildings with the usual attitude ‘God forbid some human presence might distract from the sculptural qualities of my architecture’ – SITE tries to conscientiously include participants in pictures of our buildings and spaces, just to demonstrate how necessary they are to the full social and aesthetic experience.

From the Catalogue for the Victoria and Albert Museum Post-Modern Exhibition in 2011 ‘Arch-Art’ (Foreword essay) – (not yet published), 2010.